The first day we met, Samin Nosrat improved my cooking for maybe the 100th time. I’d been employing Nosrat’s approach to cooking in my own kitchen for more than a year, each small tweak and lesson learned its own miracle. But last month, Nosrat intervened directly (and perhaps unknowingly).

At the market she chose as our meeting place, downtown Brooklyn’s Atlantic Fruit & Vegetable, the Berkeley-based chef and educator giddily pointed out a number of produce gems. One of them—fresh bay leaves—ended up finding its way into the soup I made that evening. A spicy medley of andouille sausage, Yukon Gold potatoes, black-eyed peas, and Tuscan kale, my soup would’ve been tasty without the addition. But the bay leaves, quietly fragrant and almost minty in their essence, balanced out the richness of the broth. Suddenly, it sang.

The author of the celebrated cookbook Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking has spent her nearly 20-year career perfecting the art of balance. For much of that time, the 38-year-old Nosrat has paired her love of cooking with an affinity for the written word. A little while after our marketplace excursion, over lunch at Yemen Café, a sparse but inviting neighborhood mainstay, Nosrat explained why she combines the two modes of expression. As we ate lentil soup, hummus with minced lamb, and fattah—a sublime dish combining bread, butter, honey, and cream—she spoke about the sensibility that has come to define her work.

“At some point, I realized food was a tool for bringing people together, for telling stories about people, for telling stories about culture,” she said. “And that’s what I really care about. So it’s only natural that they would go together.”

Throughout our lunch, Nosrat’s laughter filled the space around us. It’s the same approachable energy that animates her writing, whether in her monthly column for The New York Times Magazine, or in her James Beard Award–winning book. It’s also the spirit that Nosrat carried into her new Netflix show, Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, a docuseries based on her book. The show is part how-to guide for home cooks of all skill levels and part aspirational travelogue.

For Nosrat, food is not an esoteric discipline to be perfected so much as it is a medium of connection. Nosrat’s April 2017 book earned rave reviews (including from The Atlantic, which inspired me to purchase the guide well before I became an employee). The warmly written, pragmatic text begins its first formal section—“Salt”—with an anecdote from the Iranian American chef’s childhood in California, where frequent family trips to the Pacific Ocean shaped Nosrat’s understanding of salt as an element closely associated with the beach. Nosrat draws a connection in the book between the principles she’d later learn in her first restaurant job, at the acclaimed Berkeley café Chez Panisse, and the instinctively perfect beachside snacks her mother prepared:

Somehow, Maman always knew exactly what would taste best when we emerged: Persian cucumbers topped with sheep’s milk feta cheese rolled together in lavash bread. We chased the sandwiches with handfuls of ice-cold grapes or wedges of watermelon to quench our thirst.

That snack, eaten while my curls dripped with seawater and salt crust formed on my skin, always tasted so good. Without a doubt, the pleasures of the beach added to the magic of the experience, but it wasn’t until many years later, working at Chez Panisse, that I understood why those bites had been so perfect from a culinary point of view.

Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat is refreshing in its dual respect for encyclopedic culinary knowledge and for the more intangible pursuit of sensory satisfaction. Rather than inundate aspiring cooks with an index of glamorously photographed recipes to follow precisely, Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat offers Nosrat’s readers something much more substantial: a cooking philosophy. Alongside whimsical watercolor illustrations by Wendy MacNaughton and a foreword from Michael Pollan, Nosrat’s guide emphasizes an intuitive, elemental approach to cooking. “Anyone can cook anything and make it delicious,” Nosrat wrote in the book’s introduction. “Whether you’ve never picked up a knife or you’re an accomplished chef, there are only four basic factors that determine how good your food will taste: salt, which enhances flavor; fat, which amplifies flavor and makes appealing textures possible; acid, which brightens and balances; and heat, which ultimately determines the texture of food.”

Now Nosrat is expanding her approach—not to cooking, but to reaching a new set of would-be amateur culinarians. Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, the Netflix docuseries, ushers Nosrat onto screens—and into kitchens—in nearly 200 countries. The show consists of four installments. Each episode is named for one of the titular building blocks and follows Nosrat to a different country. In each new geography, the four elements remain the host’s “cardinal directions of cooking.”

For Nosrat, the new endeavor is exhilarating and unfamiliar in some ways, but the show’s core mission has informed her various strains of work for more than a decade. “I remember, like, in 2007, when I first started teaching cooking classes, I would teach 12 or 18 people, and I’d come home and I’d be like, Well, that was really inefficient! I spent all day teaching 12 upper-middle-class ladies some basic cooking lessons,” she recalled. “And after two or three classes, I was like, Man, if I had a TV show, I could get to so many people … Just like I had not seen a book that sets out to teach, I had not seen a show that really sets out to teach.”

The Netflix series begins with the sexiest of the four elements. “Fat: It’s nothing short of a miracle. Fat is flavor. Fat is texture,” Nosrat says in a voice-over at the beginning of the first episode. “Fat adds its own unique flavor to a dish, and it can amplify the other flavors in a recipe. Simply put, fat makes food delicious—and one of the most important things any cook can learn is how to harness its magic.”

As Nosrat speaks, tantalizing, decadently captured shots of food—cream, oil, beef, pie, butter, ice cream—occupy the frame. Soon, though, the visuals give way to the rolling hills of northern Italy. Having spent years in Italy following her introduction to cooking, Nosrat explains what drove her choice to return to the country for the series: “As I cooked and ate my way throughout the country, one thing became clear,” she says in the episode. “From cheese to salami, ragù to gelato, Italians are masters at using fat to make their food absolutely, fantastically, almost impossibly delicious.”

The episode follows Nosrat to Liguria, where she savors multiple kinds of olive oil, cheese, and pork. She is visibly delighted throughout the journey, her face conveying a sense of genuine excitement that is rare in the sometimes prim, restrained landscape of food-focused television. Nosrat doesn’t perform hyperbolic responses to food so much as she reacts with unabashed joy to the scientific—and social—wonder that is cooking.

Nosrat greets her first guide, whom the show introduces as Lidia, la nonna, with an enthusiastic embrace. By the time the two make pesto together, a dish that Nosrat says doubles as “a beautiful lesson about fat’s importance,” they’re moving in tandem so seamlessly it seems as though they’ve been cooking together for years.

Nosrat neither diminishes her own culinary expertise nor presumes to know more than her guides; her process of discovery is rewarding to watch partly because she functions as an adventurous proxy for viewers who are eager to learn the secrets of exceptional cooking made accessible. Her face is eminently expressive; when Nosrat eats something delicious, audiences will know—and want to cook some for themselves.

In each location, Nosrat takes care to highlight the knowledge of the people whose familiarity with each element is rooted in their country’s traditions. Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat is intentional both in its instructive approach to depicting cookery and in the kinds of people it highlights as instructors. In insisting on a diverse cast to buttress her own insights, Nosrat, who occupies a rare position as a woman of color hosting her own show, is also shifting the broader landscape of food media.

“I thought, This might be my only shot ever to have this, so what do I want to accomplish with this? I want to use it to amplify the voices of—and also just present—people and stories that don’t typically make it to this level of exposure and to this kind of screen time,” Nosrat said. “Specifically in the food world, that’s often women, that’s often older people, it’s often people of color, it’s often home cooks, it’s often rural people who don’t get the fancy-lighting treatment.”

“So I was like, Well, the other stuff already exists, so I’m gonna use my chance to show this stuff,” she continued. “And if this is the only shot I ever have, then I’ll be proud that I did that.”

Nosrat’s guides, who walk her through the lessons of their respective homeland’s cuisine with grace and verve, form a motley crew. The second episode, “Salt,” takes the host to the southern islands of Japan, where her friend, the chef Yuri Nomura, teaches her how to harvest hondawara seaweed to extract its salt (moshio), and Nosrat later observes the process of making miso. In the third episode, “Acid,” Doña Conchi, la abuela, teaches Nosrat how the Yucatán Peninsula’s sour oranges, salsas, and uniquely acidic Mayan honey utilize acid to create vibrant dishes, as well as the widely adapted method of escabeche. The final installment, “Heat,” brings Nosrat back home to Berkeley, where she prepares the Persian staple tahdig alongside her mother, Shahla Khazai.

Nosrat’s work to diversify the kinds of faces quite literally seen as culinary experts is directly connected to her view of food—and food stories—as a tool to both create and strengthen bonds between people. Her efforts come at a time when the restaurant industry, including those whose work orbits it, is more openly grappling with questions of power—and who holds it.

Earlier this year, the chef and author Julia Turshen created Equity at the Table, or EATT, a database of food professionals that only features people from backgrounds most often excluded from the industry’s upper echelons—namely, women, people of color, and LGBTQ individuals. EATT is a tool created explicitly as a resource for people from these communities, but Nosrat’s series echoes its intentions implicitly. By presenting women, people of color, and non-Americans as culinary experts, Nosrat both offers alternatives to the current veneration of white male chefs and makes linkages across continents by emphasizing overlaps in technique.

“There are only so many ways to cook, there are only so many ways to make food taste good,” Nosrat said. “If we can just use whatever small amount of information that we have to distill things, to understand the universal, then it’ll be a lot easier to be a good citizen of the world.”

Nosrat, in other words, sees her role as something of a conduit. Many of the lessons she imparts in both the book and the series aren’t necessarily new, but they’re reaching audiences whose relationship to the art of cooking is strained by a host of different forces.

“I think as every generation, or quarter, or half generation passes, we get more and more distant from cooking traditions that were historically passed down from generation to generation,” she said. “So maybe if I can be a surrogate granny or whatever, that can be helpful.”

“Or just even give grannies a microphone,” Nosrat continued with a laugh, before noting that she wants her show to serve as something of a virtual cooking class for “anyone who can’t afford a cooking class, anyone who doesn’t have the time to go to a cooking class, anyone who has felt intimidated by the really aspirational cooking that tends to get screen time in this world.”

Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat is directed by Caroline Suh, who also worked on the 2016 Netflix series Cooked, which followed the professor and food writer Michael Pollan as he studied the science behind cooking. “She taught Michael Pollan how to cook,” the showrunner said of Nosrat, Pollan’s former journalism student, when we spoke recently over the phone. “She’s a big part of his book, and it was very important to him that we feature her in the series.”

“Samin is very lovable, and everyone who meets her gets a lot of joy and happiness from talking to her,” Suh continued. “She has a kind of infectious happiness, so she really left a big impression.”

As Nosrat remembers it, Suh predicted the show’s existence years before it would come to fruition: “She said, Jamie Oliver was discovered sort of in the back, walking through the back of someone else’s show. This is your Jamie Oliver moment. She called it.”

Suh has worked on a wide-ranging collection of television projects. Iconoclasts, a mid-aughts production of the Sundance channel, paired “creative visionaries” like Tom Ford and Jeff Koons for lengthy conversations about their careers, inspirations, and future. For Suh, the challenge of adapting Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat was a welcome one.

Suh wanted the show to convey the same energy as Nosrat’s home, the host noted, so the director asked her to send mood boards, textiles, and lists of things she loved. Suh came up with the idea of incorporating archival imagery into the show: The effect is almost collage-like, a balance to the rich food and travel scenes.

“Anytime I’d show anyone footage, or anytime I showed anyone the trailers, any of my friends—every single person I know, every single person—their first response is, Oh my gosh, it’s really you! They really got you,” Nosrat recalled with a laugh. “And to me, I’m always like, Who were you expecting?”

Nosrat is quick to offer praise for just how well Suh distilled her “essence,” despite having initially been taken aback by how much of the show is based on her persona. It’s an effective aesthetic, and philosophical, premise: Nosrat exudes California effervescence. She’s not prissy, but she’s attentive to details. In capturing the things Nosrat loves most, the show offers a balanced visual language that resists both overly indulgent viewing and scant production.

“The beautiful stuff tends to be aspirational,” Nosrat said. “It’s like Chef’s Table and you’re like, Ooh, maybe one day I can save up and go eat at this $1,000 dinner or something, and then the accessible stuff doesn’t really have a sensory focus.”

“So why is the beautiful stuff not for everybody? Why can’t it be for everyone?” Nosrat continued. “Why can’t there be a show that doesn’t intimidate you, but also is so gorgeous that it inspires you to want to get up and do the stuff?”

Months after the end of production, there’s one recipe that’s stuck with Suh. The director, who saw Nosrat’s wide range of influences as a “huge opportunity to bring places and people to the screen who weren’t the usual suspects,” was surprised to find herself drawn to one of the simplest moments in the series.

“I love the scene where she makes focaccia. That to me is such a simple scene and it almost happens in real time, and it just shows how much care and beauty is in this one very simple thing,” Suh said. “And to be honest, I did not like focaccia before and it was so delicious that now I kind of search it out wherever it’s available.”

“I would make the pesto, that would be my unsolicited advice to people,” Suh added. “Because the pesto is super easy and I think it’s so much more delicious than store-bought pesto.”

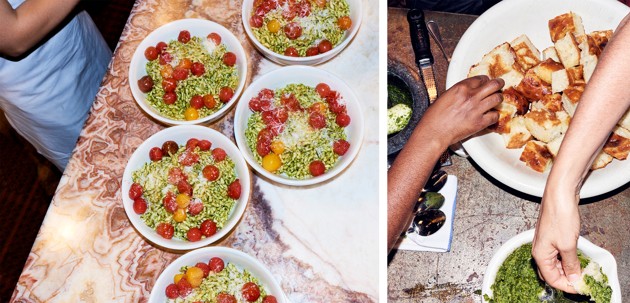

On a recent night, in Brooklyn’s waterside Red Hook neighborhood, Nosrat prepared the same pesto in front of a small audience. During the dinner held to celebrate her show’s release, Nosrat laughed often—especially as she called on a guest to help her grind basil leaves into a paste. Soon, the entire space was filled with both Nosrat’s exclamations and the herb’s distinct fragrance.

When the finished pesto was served to guests, alongside the same kind of focaccia Nosrat prepared in the first installment of the series, it disappeared almost impossibly quickly. Suh, who was in attendance, had been right in her assessment. The pesto is clean and bright; the delicacy of the basil perfectly complements the overlapping salts and fats of all the cheese it employs. To compare it to store-bought versions, which I’ve been known to indulge in during distinctly un–Ina Garten stages of life, would be an insult.

But more importantly, the experience of crowding around—and marveling over—the pesto brought the evening’s guests together. Many of us were strangers before the evening, but our appreciation of Nosrat’s talent and generosity made us a kind of family—along with some help from a decadent but not quite sybaritic menu: trofie with cherry tomatoes and pesto; buttermilk chicken; chicory salad with pears, dates, and mustard vinaigrette; delicata squash with labne, honey, chili, and sesame seeds; harissa; and eton mess with plums, apricots, and pistachios.

Even as I ate my body weight in food I knew I wouldn’t soon forget (and carried away two jars of pesto to share with my roommates later that evening), something Nosrat said during our earlier conversation stayed with me. Perhaps there was a fifth element, something that enhanced the appreciation cooks and diners have for the first four.

“There’s so many meals I’ve had where I don’t remember anything about what I ate,” she said then. “I just remember how I felt at the table, who I talked to, what we talked about—that’s what I find to be the best part of eating.”